The national reporting framework

Building block A: Country and VET overview

A.1: Country background

A.1.1 Introduction

Following national elections held in June 2017, the incumbent government was elected in September 2017 by a wide coalition of political parties forming a tight majority in the Kosovo Assembly. The Government Programme for the period 2017-2021 is built on four pillars:

- Rule of Law with focus on combating corruption and organised crime, by introducing changes in legislations and conducting full functional review of the Rule of Law sector;

- Economic Development and Employment - aiming at ensuring sustainable economic development with the average growth rate of 5-7%;

- Euro-Atlantic Integration – strengthening Kosovo’s position in the international community by increasing number of recognitions by other countries and ensuring membership in relevant international organisations;

- Sectorial Development – the focus is on the following sectors: Education, Health, Social Welfare, Environment and spatial planning, as well as Culture, Youth and Sports;

According to IMF, Kosovo’s economic growth in 2018 is expected to be among the highest in the Western Balkans Region – 4%, whereas for 2019 it is projected at 4.2%, due to expected acceleration in public investment . However, as outlined in the report, pressures for higher social benefit spending are likely to increase the fiscal deficit.

Development of the Human Capital is the first pillar of the Kosovo’s Development Strategy 2016-2021 (NDS) . The interventions directly linked to Education and Employment include:

1) enhancing the quality of teaching and learning in school’s system;

2) linking education programmes with the labour market demands;

3) improving testing, inspection and accreditation in the education sector;

4) optimising expenditures in education by advancing data collection systems;

5) addressing informal employment and creating adequate working conditions for employees.

Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2017-2021 (KESP) is the basic document for the development of the education sector in Kosovo. The document was developed in the period June 2015-July 2016 through a highly participatory process led by MEST, and based on the assessment of the previous strategic plan – KESP 2011-2016. In general terms, the development of the KESP took place in the context of an awareness of the four common EU objectives to address challenges in education and training systems by 2020, detailed in Education and Training 2020 (ET 2020) . Vocational Education and Training is one of the seven areas of KESP, and the main challenges to be addressed in this field are: 1) Non-compliance of VET programmes with labour market requirements; 2) Difficulties in provision of teaching materials for VET; 3) Lack of VET core curriculum; 4) Serious flaws in internship and professional practice; 5) Lack of career guidance and counselling.

Increasing employment and developing skills in line with demands of the labour market is one of the four objectives of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare (MLSW) Sector Strategy for the period 2018-2022 .

The main challenges in this field to be addressed by the Strategy are: 1) Limited inclusion of unemployed people in employment services and 2) ALMMs, with particular focus on women and young people

Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) anticipates cooperation between Kosovo and the EU in raising the level of general education and vocational education and training, as means to promote skills development, employability, social inclusion and economic development.

European Reform Agenda (ERA) calls for an urgent education reform which would link postsecondary education and training with gaps in the labour market and quality improvement of pre-university education while the immediate and medium-term priorities in this area, improve the quality of higher education and VET. On the other hand, Economic Reform Programme (ERP) includes actions from the NDS agenda as well as sectorial strategies that require focus in order to remove current or potential obstacles in the field of education and skills, focusing on three reform measures: 1) Harmonisation of skills supply and demand by drafting occupational standards and reviewing curricula; 2) Reform in Pre-University Education by implementing competency-based curricula and introducing the teachers’ career system; 3) Increasing the Quality and Competitiveness in Higher Education by developing mechanisms for quality assurance, ranking, quality-based funding, linking higher education programs to labour market demands and improving career orientation services.

A.2: Overview of Vocational Education and Training

A.2.1 Overview of VET: set-up and regulatory framework

The Law defines VET as activity that “aims to equip students/candidates with knowledge, practical ability, skills and required competencies in specific occupations or wider in the labour market” . The Law sets the following principles for the VET in Kosovo: inclusion; access, transfer and progress; theoretical learning and professional practice; current and future needs of the economy; supporting career development as integrated part of lifelong learning . Further, activity fields of vocational education and training are defined as follows :

- development of competencies and training for employment of individuals in accordance with occupation and their career according to the labour market;

- creation of general and professional culture in accordance with principles of lifelong learning education and economical, scientific and technological developments;

- recognition of the individuals’ competencies based in occupational standards of the relevant level.

The VET system consists of formal and non-formal provision. According to the Law on Qualifications “Formal education” refers to approved education programs provided by licensed educational institutions and using curricula approved by the MEST. Such programs are offered by secondary vocational schools (ISCED 3) and specialized post-secondary institutions accredited by the National Qualifications Authority (ISCED 5). As indicated in an NQA publication , non-formal VET provision includes:

- Vocational training (employment or job‐related), provided in both public and private vocational training centres, and in employment);

- Adult compensatory education courses for those with uncompleted primary or secondary education, based on formal education programmes and offered mainly by schools;

- Other diverse kinds of adult learning provision in areas such as foreign languages, ICT, handicrafts, arts, music and culture etc. offered by private providers, NGOs etc.

In the Kosovo system, a qualification is defined as an official recognition of achievement that indicates completion of education or training or satisfactory performance in a test or examination. This qualification process leads to the issue of a certificate and provides basis for progression to work or further learning for individuals. Qualifications in VET are categorized based on the type of provision (formal and non-formal). The qualifications based on the formal provision and non-formal provision are further defined based on the content such as educational subjects, an occupational profile, a skill set related to a work role, and are divided into three groups: National Combined Qualifications, National Vocational Qualifications and Qualifications based on international standards. Figure 1. Links between NQF levels and Kosovo’s education and training structure on the one hand, and with occupational requirements on the other.(see in the report in PDF p.8).

The basic structure of the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) consists of eight levels at which qualifications, and modules or other components of qualifications can be placed (Figure 1). They progress from the simplest levels of achievement to the most difficult and complex. Each of the levels of the NQF is defined by a statement of typical outcomes of learning based on the approach adopted by the EQF, providing a cross reference to the levels of the EQF. Kosovo NQF level descriptors are based on the EQF level descriptors, elaborated to show how they apply in the Kosovo context.

NQF was completed in 2011 and formally linked (“referenced”) to EQF in 2016 .

As shown in Figure 2, general entrance requirement for ISCED 3 level vocational programs (NQF 4) is completed compulsory education (NQF 2). Upon successful completion of the final exam, students receive vocational diploma19. The latter represents an entrance requirement for tertiary vocational programs (NQF 5) which usually last 1-2 years (60-120 ECTS) and end with tertiary vocational diploma. (see Fig.2 in the report in PDF p.9).

Formal VET provision

It is estimated there are 140 profiles at ISCED 3 level, categorised in 17 vocational fields, although data for the school year 2017/18 show enrolments in 119 profiles only . The Curriculum Framework for vocational education is currently being developed and will provide classification of profiles by broader fields. However, with help from the ALLED project , the MEST Division for Vocational Education has adapted a methodology for categorising the profiles by using the ISCED-F coding system which defines 10 broader fields: 1) Education, 2) Arts and Humanities, 3) Social sciences, journalism and information, 4) Business, administration and law, 5) Natural sciences, mathematics and statistics, 6) Information and Communication Technology (ICT), 7) Engineering, manufacturing and construction, 8) Agriculture, forestry, fisheries and veterinary, 9) Health and welfare, and 10) Services.

In the field of formal VET provision, NQA has validated 5 tertiary vocational qualifications (ISCED 5) offered by 3 accredited providers .

Non-Formal VET provision

Qualifications of non‐formal VET for adults may use national standards (National Vocational Qualifications), international standards (Qualifications based on International Standards), the standards required by particular employers (Tailored Qualifications). The non-formal qualifications can range from level 2 to level 7 of the NQF.

NQA has validated and approved 51 qualifications of levels 2-5 offered by 50 accredited providers24.

The legislative framework for Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Kosovo consists of the following set of laws:

- Law No. 04/L-032 on Pre-University Education -Basic Law which sets that the most important responsibilities of the central Government in administering the Education System are: to develop policies, draft, and implement legislation; to promote a non-discriminatory education system and protection of vulnerable groups; to manage a system of licensing and certification of all teachers; to set the criteria for the evaluation and assessment of pupils in educational and/or training institutions; to organise and manage external assessment, and so on.

- Law No.03/L-068 on Education in the Municipalities of the Republic of Kosovo. This Law devolves certain responsibilities for managing Education System from central to local level, and is part of a larger decentralization package. Also, the Law regulates special rights of the Serbian community to use curricula and textbooks from the Republic of Serbia.

- Law No. 04/L-183 on the Vocational Education and Training -This Law sets out the structures of the institutions which deal with this type of education and training. The VET law envisages a combination of school-based and work-based training.

- Law No. 05/L-018 on State Matura Exam -Introduces non-compulsory State Matura exam for general secondary schools and vocational schools graduates who want to continue their university studies.

- Law No. 03/L-060 on National Qualifications -The purpose of the Law was to establish a national qualifications system based on a National Qualifications Framework (NQF) and regulated by the National Qualifications Authority (NQA).

- Law No. 04/L-143 on Adult Education and Training in the Republic Of Kosovo -Regulates the governance and financing of the adult education and training in Kosovo.

- Law No. 06/L-046 on Education Inspectorate in the Republic of Kosovo -Determines authority, responsibilities and organisation of the Education Inspectorate in the Republic of Kosovo.

- Law No.03/L –212 on Labour - Basic Law regulating the rights and obligations deriving from employment in Kosovo.

- Law No. 04/L-083 for registration and records of the unemployed and jobseekers -Regulates the methods, procedures, conditions for the registration and de-registration of unemployed and jobseekers in Kosovo, as well as intermediation of employment, professional orientation and educational activity aiming to increase the employment.

- Law No. 03/L-019 on vocational training, rehabilitation and employment of people with disabilities -Rules and determines the rights, conditions, forms of vocational training, rehabilitation and employment of people with disabilities, for their integration in open labour market according to general and special conditions laid down by applicable legislation.

- Law No. 04/L-205 on the Employment Agency of the Republic of Kosovo -This law regulates the establishment, organisation, functions, duties, responsibilities and funding of the Employment Agency of the Republic of Kosovo, including its role in the provision of vocational training.

Secondary legislations consist of numerous administrative instructions issued by the MEST and MLSW, as well as regulations approved by the relevant agencies: National Qualification Authority (NQA), Agency for Vocational Education and Training and Adult Education (AVETA) and Employment Agency of the Republic of Kosovo (EARK). References to secondary legislation will be provided in the relevant parts of this report.

A.2.2 Institutional and governance arrangements

Government of Kosovo manages VET sector through ministries and agencies operating under ministerial supervision.

The Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST) is responsible for: overall education policy and legislation, including VET, higher education and life-long learning, research and development and libraries. Although, VET Law recognises prerogatives of other ministries and government agencies to participate in managing the VET system in Kosovo, MEST, in cooperation with MLSW, is effectively in charge. Based on recommendations of the EU supported functional review of the MEST , the Government of Kosovo approved a new regulation for internal organisation of MEST , which establishes a separate department for VET with three divisions: Division for School Infrastructure, Curricula and Labour Market Analyses, Division for VET Standards and Quality Assurance, Division for Lifelong Learning.

According to the Law11, Agency for Vocational Education and Training and for Adults (AVETA) is responsible for administration and leadership of Institutions of Vocational Education Training and for Adults regarding the financial, human sources, construction of buildings and infrastructure of all public VET institutions under its regulatory administration. AVETA currently manages 6 such institutions, whereas the rest operate under the authority of respective municipal education directorates.

Council of Vocational Educational and Training and for Adults (CVETA) is an advisory body to MEST. Among others, CVETA advises the MEST on the general direction for vocational education and training and adults’ education policy in Kosovo and has authority to approve occupational standards . Although, CVETA was established in 2014, the Council is currently not operational, primarily due to the fact that its members are not getting compensated for their service .

National Qualifications Authority (NQA) is an independent public body, established in accordance with the Law . NQA was established by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST), and acts in agreement with the Office of the Prime Minister and other relevant ministries. The NQA Governing Board consists of 13 members, representing ministries, organisations, social partners and universities. NQA responsibility entails oversight of national qualifications along with the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Agency for Accreditation and other professional bodies, as well responsibility for professional qualifications.

The Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare mandate is based on functions in the area of the welfare state and the labour market, that are: employment and labour market issues; including vocational training, social protection and social transfers: from pensions to poverty relief; assistance to the disabled. Due to Kosovo’s recent history, the MLSW has a function of providing care for war martyrs’ families and civilian victims. Vocational Training function is performed under the Department of Labour and Employment which has a special division for that purpose . Among others, MLSW is expected to conduct analyses of the labour market needs and support the MEST, in planning to meet the needs for vocational education and training. Also, MLSW, in cooperation with Kosovo Agency of Statistics, is responsible for classification of occupations .

Employment Agency of the Republic of Kosovo (EARK) is the public provider of services in the labour market, responsible for implementing employment and vocational training policies . The agency provides its services through 38 employment offices at municipal level and 8 regional vocational training centres (VTC).

Municipalities are responsible for operation of public educational institutions, including vocational schools. Their responsibilities include: construction of education facilities, enrolment of students, employment of teaching and management staff, training, supervision, and so on. Municipalities have education directorates, whereas directors are appointed by mayors.

A.2.3 Basic statistics on VET

There are 68 vocational schools in Kosovo offering ISCED 3 level programs of which 6 are directly managed by AVETA, whereas 62 others by the respective municipal authorities. Table 1 provides overview of enrolments in VET schools by ISCED-F broad fields of study and sex in the last five years.

According to the data provided by MEST, there are 3,154 teachers in VET schools, of whom 1,287 female47 . Table 2 provides an overview of public expenditures in Vocational Education in the last 4 school years. The proportion of salaries in overall expenditures appears to be very high. As a rule, VET related expenditures are not properly registered in the Government accounting system, and therefore are difficult to be tracked.

Continuous Vocational Education and Training (CVET)

According to the EARK, participation in vocational training declined in 2017 compared to the previous year – 5,979 job-seekers started training in one of the eight VTCs (of whom 33.9% women), compared to 6,736 in 2016. The report indicates that 39.6% of trainees where of the age 15-24, whereas 43.2% between 25 and 39 years of age.

The Vocational Training Division at EARK has currently 92 staff members of whom around 60 trainers based in VTCs. The 2017 budget was 1.22 mil. EUR, whereas in 2018 it decreased to 1.02 mil. EUR .

CVET takes place in a number of other private institutions, but participation data are not available.

A.2.4 Vision for VET and major reform undertakings

Kosovo Education Strategic Plan 2017-2021 (KESP) has a separate chapter on VET. The VET related strategic objective is “Harmonising vocational education and training with labour market requirements in the country and abroad, and creating an open system for adult education”. The strategic focus is on improving the relevance of school programs to labour market needs; the development of a VET specific core curriculum, aligned to the Kosovo Curriculum Framework (KCF); the systematic provision of high quality work experience and professional practice; and, specific to the Kosovo context, ensuring the sustainability of the Centres of Competence and their further development. In terms of Adult Education, the focus is on establishing an efficient and quality adult education system. There are 9 expected results deriving from the VET strategic objective, and for each result a number of measures (activities) leading to its achievement are identified.

For each strategic objective an action plan was developed, as well as indicators of success to be used for monitoring the implementation of KESP. The action plan for VET comprises a total of 43 measures (activities) with clear schedule and assigned responsibilities for implementation. The estimated cost for implementation of planned measures is € 6.78 mil. of which € 4.7 mil. should be provided from the Kosovo Budget. Table 3 provides an overview of indicators and targets for the VET-related strategic objective of KESP.

The findings of a monitoring carried out by a Consortium of CSOs conclude there is a stagnation in the implementation of the KESP during 2017, and this is not related only to the shortage of budget, but also to organisational issues. Regarding progress in the implementation of measures related to VET, the report concludes:

• “Around 47% of the upper secondary vocational education students attend learning in economic-law and health care sectors, with significantly lower opportunities for employment, whereas the number of students with better prospects for employment continues to remain below the desired level. There are no proper actions by MEST and MEDs to change this situation.

• Appropriate teaching and learning materials are available for 24 out of 135 profiles of vocational education, while in other profiles there is a kind of "improvisation" with the materials prepared by teachers, materials which have not gone through any verification process. There is stagnation in addressing this problem.

• Participation of girls in secondary vocational education is not at the desired level, and a high representation of males is noted in all profiles leading to the so-called qualifications "reserved for men".

• There are suitable teaching and learning materials available for 24 out of 135 profiles of vocational education, while in other profiles, there is a kind of "improvisation" by using materials prepared by teachers, which have not gone through any verification process. There is stagnation in addressing this problem.

• With few exceptions, career counselling and guidance is not present in vocational schools in Kosovo. However, preparations are being made to provide a level 5 qualification for career counsellors.

• EMIS has started to collect data on adult education in Kosovo. During the academic year 2016/17, 1,794 adults were included in secondary vocational education, of whom 617 female. Unfortunately, there are no data on the inclusion of adults in various forms of informal education Information from the field reveal serious problems in implementing professional practice and supporting this aspect of student development by schools. With few exceptions, Career counselling and guidance continues to be absent in vocational schools in Kosovo.

• Despite the progress made in providing programs for adults, adult education remains the most underdeveloped sector in the education system, since the necessary preconditions for its management have not been established yet.”

Two out of ten recommendations of the monitoring study53 call for special mention: 1) MEST should establish a mechanism to coordinate implementation of the KESP 2017-2021, led by the Minister or a Deputy Minister, with participation of senior officials at MEST; 2) Network of vocational schools and the profiles offered should be reviewed in order to avoid creating structural unemployment by enrolling large numbers of students in profiles with limited employment prospects. Also, it is necessary to improve practical training and career counselling in vocational schools.

Our informants agree that the VET reforms in last few years are not of substantial nature, but rather represent revision of the existing structures. New VET Core Curriculum was in the centre of discussions in last two years and the first draft has already been circulated, although not all parties were satisfied with its concept and quality, primarily due to the fact that there is one Core Curriculum for all VET fields. Delays in approving the new core curriculum for VET affect the alignment of VET programs with Labour Market needs. Another important undertaking is the work on revising VET funding formula, which is supported by wider donor community and coordinated by Lux Development.56 Error! Bookmark not defined.

On the other hand, establishment of EARK and separation of policy making and executive functions with MLSW is considered to be a major step forward. EARK effectively operates the eight VTCs offering 30 different profiles. There were positive steps in the process of accreditation of VET providers and programs by the NQA, which contributed to the improvement of the quality assurance procedures within the VET institutions opting for accreditation

A.3: The context of VET

A.3.1 Socioeconomic context

Kosovo’s economy remains heavily consumption-led, with remittances and government expenditure accounting for approximately 40 percent of its GDP. The recent EU progress report appreciates the progress in developing a functioning market economy and improvements in the business environment, but emphasizes that the informal economy remains widespread. Nevertheless, Kosovo remains one of the poorest countries in Europe and has the lowest level of per capita gross domestic product (GDP) in the Western Balkans. Despite recent progress in the Doing Business Ranking, the business environment in Kosovo is weak mainly due to poor governance, an erratic and insufficient supply of electricity, and lack of an adequately trained workforce.63 The perception of a weak “rule of law” impedes initiatives for foreign investments and supports small scale low value added production, instead of more competitive companies.

Despite some progress, there seem to be no major developments that could significantly affect the structure of the economy and demand for skills. Certain sectors like agriculture, manufacturing and IT seem to be experiencing positive trends (partly due to donor support), however the economy is still dominated by low value added services.54 Some sectors are already facing skills shortages due to their maturing and participation in international competition. There are no tracer studies in Kosovo that would provide additional information on demand for skills, and also a good mapping of economic priorities at local level is missing.58

The 2017 national elections produced a largely inconclusive mandate for forming a Government, which resulted in a wide coalition of political parties with unclear parliamentary majority to make key decisions supporting economic development. The number of government ministries was increased from 19 to 21, whereas 79 deputy ministers have been appointed to date . Nevertheless, national elections as well as subsequent local elections sent an unambiguous message that the voters want a change in the society. Continuous politicization of public administration to satisfy interests of coalitions at central and local level, as well as insufficient progress in fighting high level corruption, are among major factors impeding social and economic development of the country.

A.3.2 Migration and refugee flows

Migration to Western Europe, both legal and illegal, is quite widespread in Kosovo and is caused by political and socio-economic circumstances. It is estimated that 122,657 citizens or 6.9% of the resident population migrated from Kosovo in the period 2012-2016 , of them 22,012 in 2016. In the same period, 48,070 migrants, mostly those who were denied residence, returned to Kosovo. In 2016, Kosovo is listed among top ten countries whose migrants have benefited from IOM assisted voluntary return and reintegration programs, which include pre-departure assistance as provision of re-integration assistance. IOM notes that one of the reasons for migration is “the lack of confidence in the future of the country and its economy amongst especially those Albanian Kosovars with higher levels of education”75. Emigration aspirations have returned to levels not seen since before independence, a trend that may itself fuel an even greater demand to leave the country. Anecdotal evidence suggests emigration trends seem to remain significant and, as opposed to earlier periods, recently increasingly young professionals are seeking to leave the country

A.3.3 Education sector context

The general structure of the Education System in Kosovo is outlined in Figure 3 below. Compulsory Education starts at the age of 6 with primary level (grades 1-5, ISCED 1) and continues with lower secondary level (grades 6-9, ISCED 2). Upper secondary education (grades 10-12, ISCED 3) is not compulsory and is divided into two main streams: General Secondary Education (Gymnasia) and Vocational Education. Graduates from either stream need to complete state Matura exam to gain access to the University (Bachelor level, ISCED 6, EQF 6). Graduates from vocational schools may pursue studies in tertiary vocational programs (ISCED 5, EQF 5), in which case state Matura exam is not required.

In the school year 2017/18, 53% of upper secondary students enrolled in VET schools, whereas 47% in general schools (gymnasia) . On the other hand, 40.7% of students in vocational schools are girls, whereas in gymnasia 58.2%76. Since there are no tracer studies carried out in vocational schools it is virtually impossible to estimate number of VET graduates having used various progression routes available within the Kosovo Education System. However, it is indicative that 24,152 students were expected to graduate from secondary schools in Kosovo (both gymnasia and VET schools) in the school year 2016/17 , whereas 23,524 students enrolled in the first year of Bachelor studies in the academic year 2017/1876, which constitutes 97.4% of secondary school graduates.

In 2016, MEST approved the revised version of the Kosovo Curriculum Framework (KCF) , which represents a major departure from content-based to competency-based curriculum. The KCF is designed in six curriculum key stages representing periods with common features in terms of children’s development and curriculum requirements. They constitute the main reference points for defining key competencies to be mastered, student progress and achievement requirements, the organization of learning experiences, access and assessment criteria, as well as specifying the institution responsible for their achievement. The structure and organization of the curriculum according to curriculum key stages is shown in Table 4 (see in the report in PDF p.19).

In addition to KCF, which defines competencies and learning fields, core curricula of General Education (ISCED level 1-3) are developed, effectively translating competencies into learning outcomes and setting the stage for development of subject syllabi. The hierarchy of curriculum documents in relation to learning outcomes is lustrated in Table 5.

A.3.4 Lifelong learning context

Lifelong Learning does not appear to be a policy priority in Kosovo, and the reason for that is described in the Kosovo Education Strategic Plan:

“In terms of Adult Learning, there is awareness that ‘Making lifelong learning and mobility a reality is the first objective of ET 2020. However, the almost total lack of structures and expertise in the field of adult learning in Kosovo combined with the pressing need to improve the quality of statutory provision, means that it is not feasible to prioritise developments in LLL in Kosovo in the short and medium term. Nonetheless, there will be some attempts via KESP 2017-2021 to begin to tackle this area.”

From the policy perspective, LLL is restricted to creating conditions for as many adults as possible to attend formal education programs. In the school year 2017/18 there were 2,270 adult learners (817 women) attending vocational programs in public VET schools , what represents an increase of 27% compared to the previous school year

A.3.5 International cooperation context: partnerships and donor support

There are currently four major projects supporting the development of the VET sector in Kosovo in the period 2017-2022 funded by the EU, as well as governments of Germany, Switzerland, Luxemburg and Austria. . Relevant information about projects in provided in the tables below.

Building block B: Economic and labour market environment

B.1: VET, economy, and labour markets

Identification of issues

B.1.1 Labour market situation

Labour market indicators for Kosovo lag considerably behind other countries in the Region and Europe. According to the Kosovo Agency of Statistics (KAS), which conducts quarterly labour force surveys, unemployment rate in Kosovo continues to be very high – 29.4% in the second quarter of 2018 , although this represents a slight improvement compared to the 2017 unemployment rate – 30.5% . There are no significant differences in the share of unemployed women and men, but this is primarily due to extremely high inactivity rate among women – 82.6% vs. 36.9% in men. In the second quarter of 2018, 35% of secondary vocational graduates where unemployed, as well as 17.5% of those with tertiary qualifications. The highest unemployment rate of 55% is recorded among youth aged 15-24 which is well above the average of the Western Balkan countries – 37.6% . Another striking feature of Kosovo youth is the exceptionally high share of youth not in employment, education or training (NEET) accounting for 30.2% of the young population as opposed to the Regional average of 23.5%.

The estimated number of employed persons decreased from 357,095 in 2017 to 341,610 in Q2 of 2018, whereas, in the same period, the inactivity rate increased from 57.2% to 59.6%. The gender gap is very high – only 12% of working age women are employed compared to 44.8% of working age men. The highest rate of employment is found among persons belonging to the age groups 35-54 (39%); for women is the age group 25-34 (16.4%) whilst for men the highest rate characterizes age group between 45-54 (66.2%). Data shows that 34.9% (M: 48%, W: 14.4%) of working age population with secondary vocational qualification are employed, as opposed to 35 % with secondary general education (gymnasia) and 66.4% with tertiary education. Whereas holders of a secondary vocational qualification are the most represented among private sector employees (43%), public sector is dominated by employees with tertiary qualifications (60.2%). The economic sectors that lead to employment are wholesale and retail trade, car and motorcycle repairs (T: 16.8% of employed, W: 18%), Education (T: 11.7%, W: 22.4%), Construction (T:11.6%, W: 1.2%) and manufacturing (T: 9.5%, W: 5.5%).

However, more optimistic estimates are provided in a study sponsored by Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) . The research team enumerated 8,533 households, collecting employment information on 32,742 individuals and completing 8,604 extended interviews. Based on Eurostat definition, the working age population was considered to be 15-74 as compared to 15-64 in the KAS methodology.Table 6 provides a comparison of results between the two surveys:

Also, this study provides a different picture of employment by economic sectors with most jobs offered in Agriculture (T: 21.7%, W: 33.3%), followed by Construction (T:13.9%, W: 0.6%) and other service activities (T:13.7%, W: 14.3%).

According to the authors of this study: “The primary driver of this divergence is likely the higher rates of agricultural and unpaid family workers captured by this study. These individuals seem to have been classified as economically inactive in past estimates, artificially dampening employment rates. It should also be noted that past estimates are substantially more aligned with the colloquial, rather than economic, definition of employment.”

The divergence of results between the two studies may also be due to high levels of informal employment in Kosovo. The UNDP Human Development Report 2012 estimated that between 30% and 40% of the Kosovo labour market is informal. The Business Informality report also estimates that 37% of the total employed workforce is not declared since businesses try to avoid taxes and regulations. This is particularly true in the agricultural sector. Often for the labour market entrants (especially women and youth) the informal sector is the only way to find a job in an economy that provides extremely limited numbers of jobs. On the other hand, 68.2% of business owners reported that their employees asked to be paid in cash rather than through bank transfers, in order to avoid income tax and pension contribution and to retain more cash on hand.

As indicated in the Economic Reform Programme (ERP) , the unfavourable situation in the labour market is a result of many related obstacles. On the demand side, low economic development, lack of growing firms and widespread informality result in low job creation in private sector. It is estimated that over 90% of registered companies in Kosovo are micro-enterprises, employing less than 10 people . According to a World Bank report , only 4% of companies that started as micro-enterprises grew within 5 years, thus providing limited job opportunities. The small domestic market and limited integration are important constraints to growth. Dissatisfaction with socio-economic conditions and lack of employment opportunities has also fuelled emigration – mainly illegal migration to the European Union.

On the supply side, non-adequate development of vocational training system, including the integration of learning with work and discrepancy between curricula content and market needs, result in mismatch between the supply of skills and the labour market needs.94 The differences in employment by education levels indicate an existence of a skills mismatch which was confirmed in a 2015 survey among Kosovar business companies. A majority of firms reported lack of the required skills and work experience as the two main problems when hiring. What is more concerning, is the fact that the private sector reports a lack of skills relevant for the labour market even for the occupations which are oversupplied. Skills found lacking by companies spread over a wide range of professions (technicians, professionals, managers, clerical and service workers, agricultural, construction and craft workers) and areas (languages, computers, soft skills).

B.1.2 Specific challenges and opportunities: skill mismatch

The links between the Kosovo’s economy and the country’s education system are still weak. The private sector still has difficulties to define its needs, and the schools – both for VET and HE – are not yet in a position to provide the labour market with potential employees who had undergone practice oriented training and whose skills make them immediately attractive for future employers. Many companies report problems hiring new employees, largely because of insufficient experience or skills, and consider this kind of constraint as impediment for their growth. On the other hand, there is a general distrust of companies towards the VET sector in Kosovo. Well-established and export oriented companies emphasize the need to make significant investment in providing remedial training to their staff.

Table 7 shows share of students enrolled in VET schools in Kosovo by broad fields of study, as defined in ISCED-F. Approximately 1/3 of VET students have enrolled in Engineering, manufacturing and construction profiles. As the percentage of students studying Business, Administration and Law has been moderately decreasing in the last 5 years, it still remains quite high – 28.27% in 2018/19, given the fact that Business and administration is important but is only a supporting element of business development. On the other hand, there is a clear trend of increased interest in health profiles, probably due to job opportunities for health professionals in some EU member states.

Table 7. Share of students enrolled in VET schools by ISCED-F broad fields of study

We have analysed enrolment data by Regions for the three fields which account for almost 80% of students: Business administration and law; Engineering, manufacturing and construction; as well as Health and welfare. In all three fields considerable discrepancies in enrolment among the seven Kosovo regions are observed (Figure 4). For example, Gjakova Region is characterized by extremely high enrolment of students in Business, administration and law profiles and lowest enrolment in the Engineering, manufacturing and construction profiles. On the other hand, in the Prishtina Region with the most developed health sector, slightly more than 10% of VET students attend health and welfare profiles, whereas in the Prizren Region, more that 25% are enrolled in those profiles. Due to the lack of tracer studies it is difficult to conclude how are these differences reflected in employability of graduates, but the differences among regions cannot be explained by trends in local economy.

Figure 4. Share of students enrolled in three most popular study fields by Kosovo Regions

In a survey conducted with 200 companies from the Trade, Manufacturing and Services sector , only 6.2% of respondents reported to be fully satisfied with skills of employees in entry level positions, whereas 41.6% were either not very satisfied or unsatisfied, with considerable gap noted in both technical and soft skills. Depending on the sector, between 55 and 70 per cent of businesses surveyed consider that the skills gap is caused by education institutions failing to produce candidates with relevant skill sets. The businesses surveyed were asked to rate the importance of given skills to their company and then the abundance of those skills in the company and the labour market. For each skill, importance and abundance were rated at the scale 1-10, computing the gap for each skill and average skills gap for each sector. The largest skills gap index (1.41) resulted in the Services sector with Time management, innovation skills, and planning and forecasting listed as the most lacking skills.

B.1.3 Specific challenges and opportunities: migration

There is a general agreement that migration of skilled labour force may cause skills’ shortages and impede the economic development, although benefits of the country from increased remittances and potential investments by Diaspora should not be undermined. Kosovo businesses have already expressed their concern for shortage of skills in the sectors of Construction, Health and Hospitality, which is largely attributed to migration. Also, there is a strong perception that this trend will continue due to the needs of developed countries for skilled labour force, with those unskilled risked to be left behind

B.1.4 Specific challenges and opportunities: digital transformation

Kosovo is a country with a high rate of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) use. According to a report of the Kosovo Association of Information and Communication Technology (STIKK) , it is estimated that 76.6% of Kosovo population are Internet users, mainly for entertainment purposes. This is at the level of developed countries. Various studies have identified ICT as one of the most interesting sectors for investment, whereas overall application of ICT by the industry remains limited, since companies have not captured appropriately its competitive benefits.

The education system has low access to information and communication technology (ICT) and contemporary technology is not integrated appropriately in curriculum, teaching or education system management. The computer-pupil ratio in Kosovo is 1:46 and much lower compared to the EU average where 3-7 pupils use a computer. The integration of ICT in learning and teaching remains an important priority that needs to be addressed in the near future, although ICT is already included in the “Life and Work” field of the new Curriculum Framework.

Description of policies

B.1.5 Strategic policy responses involving education and VET

Better linkage between Education and Labour Market is one of the key strategic measures within the Human Development pillar of the NDS with the following activities related to VET:

- Expedite the process of professional standards development, in conformity with the European Qualification Framework (EQF) as well as National Qualifications Framework (NQF), as well as the revised National Occupations Classification System.

- Determining high priority areas in Vocational Education and Training (VET) through consultation with Kosovo’s development policies and priority sectors. Development and implementation of core curricula in modular form, in line with VET priority areas and implementation of VET teacher training programmes for these sectors, based on occupational standards.

- Implementation of the combined VET pilot system with elements of dual learning (combination of learning in schools and in enterprises) starting with VET priority areas and in compliance with core curriculum. Coordinate the pay subsidization system with priority areas, in order to allow better integration of VET graduates into the labour market.

- Development and implementation of the National Skills Forecast System. This will be done by ensuring connection with the career orientation systems inside the schools and employment services/lifelong learning services. Create conditions for support services and studies in order to track career progress.

- Based on the KESP 2017-2021, the Government is working on the following areas:

- Review of the profiles provided in VET schools and adjustment to market needs and development of professional standards;

- Needs analysis conducted at the local level to meet the conditions for providing profiles from the revised list;

- Collection of best practice models of existing teaching materials prepared by teachers of different profiles;

- Development of the Core Curriculum for VET;

- Development of a Regulation on the Protection of Students’ Health during Internship;

- Review of curricula of VET institutions that provide adult education.

ERP 2018-2020 brings the reform measure #16- ”Harmonization of skills supply and demand by drafting occupational standards and reviewing curricula” which consists of the following activities :

1) Development of occupational standards,

2)Review of VET Curricula ;

3) Training of VET teachers ;

4) Development of teaching materials to support implementation of the new curricula ;

5) Providing equipment to VET schools with priority profiles ;

6) Reviewing specific funding formula for VET based on cost per sector and profile.

Estimated cost for the period 2018-2020 is € 1.75 mil. with € 75,000 to be supported from the Kosovo budget and the rest from donor funding.

“Provision of quality vocational training services in line with demands of the labour market” is one the specific objectives of the MLSW Sector Strategy 2018-2022 . The main purpose of this specific objective is to make sure that quality training is provided for occupations in demand by the labour market. To achieve this, MLSW plans to work in developing occupational standards, reviewing training curricula, providing equipment for VTCs and further developing capacity of training staff. The total anticipated cost for implementation of activities is slightly above € 0.9 mil.

In general, the level of implementation of strategic documents in Kosovo remains very low. The main reason is continuous failure to effectively include planed strategic measures in annual plans of government ministries and other implementing agencies, and allocate needed budget and human resources. For example, the Roadmap for the NDS has not been approved yet by the Government, whereas budgets from the strategic documents are not reflected in the Medium Term Expenditure Framework neither in annual budgets approved by the Kosovo Assembly.

In order to adjust supply of training and skills to labour market demand, EU-funded ALLED Project designed a methodology for developing a sector profile . A sector profile provides labour market information which indicates the movements in employment and unemployment by occupation or groups of occupations and also shows the flows of graduates from training institutions into the labour market. Its purpose is to provide an evidence base for the planning of education and for the assessment of relevance of standards and training programmes. ALLED has also published sector profiles in the field of Agriculture, Food Processing and Mechanical Engineering.

B.1.6 The role of VET in remedies through active labour market policies (ALMPs)

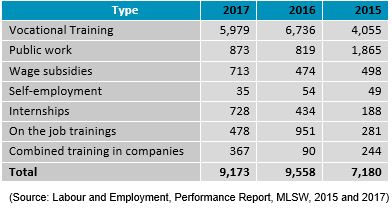

From April 2017, employment services and the active labour market measures (ALMM) for jobseekers are provided by the EARK through its mechanisms at regional/local level: 38 employment offices (EO) and 8 VTCs. EOs register and profile the unemployed and other job seekers, and provide counselling and mediation in regular employment or access to ALMM such as wage subsidies, internships, etc., while VTCs provide vocational training and retraining through modular short-term training. Table 8 provides and overview of ALMM as reported by MLSW and EARK . Most job-seekers targeted by ALMM have benefited from vocational training (65.2% in 2017, 70.5% in 2016 and 56.5% in 2015), whereas smaller numbers were exposed to on the job training and combined training in companies as shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Job seekers having benefited from Active Labour Market Measures

MLSW Sector Strategy anticipates increased provision of ALMMs with support from donors. The idea is to introduce new ALMMs (e.g. promotion of social entrepreneurship), and improve their performance through regular monitoring and evaluation of their impact on sustainable employment of beneficiaries. For this purpose, MLSW plans to develop a module for monitoring and evaluation within the Employment Management Information System (EMIS). As part of this strategy, improved employment of women will be achieved through more intensive inclusion in the ALMMs. Besides, a separate study will be carried out to analyse the situation and to develop specific ALMMs to address needs of women for employment.

Reform measure # 19 of the Economic Reform Programme 2018-202094 is designed to increase access of young people and women to the labour market through the provision of quality employment services, active employment measures and entrepreneurship. The planned activities include:

1) Capacity building of EARK on design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of ALMMs;

2) Implementing ALMMs for focus groups and development and implementation of the self-employment and entrepreneurship programme;

3) Support for voluntary work initiatives, contributing to youth employment;

4) Apprenticeship for newly graduated from higher education;

5) Modernisation of vocational training programs and services, including: re-validation of current profiles, development of 30 new standards, 30 curricula and 30 learning packages; and accreditation of 7 Vocational Training Centres for the recognition of prior learning, capacity building and expanding quality services in vocational training.

For implementation of activities related to functionalisation and capacity building of EARK, implementation of ALMMs including validation of new profiles, a total of € 10 mils is budget for the period 2018-2022. In addition, € 31,200 are budgeted annually for apprenticeship for newly graduated from higher education under KIESA budget.

The fact that ALMMs mostly include training is not seen in positive light by all relevant stakeholders, due to its ineffectiveness for employment. In reality, training through VTCs remains limited, and is provided at a very basic level, which is not sufficient for the requirements of most firms. The budget for expanding active labour market measures still remains low – around € 2mil., and is insufficient to address needs effectively.

B.1.7 Identification of skills demand and its bearing on VET provision

Demand for skills in the Kosovo VET system is identified based on research sponsored by MLSW, business associations and donor-funded projects. However, given ad-hoc character of such research projects, as well as their limited scope, the system needs to improve in order to provide reliable information on the needs for skills. A comprehensive labour market needs assessment sponsored by EU-funded project ALLED developed three indicators for identifying priority skill sectors in Kosovo :

1) impact of skill sectors on the economy ;

2) economic activities which have the highest HR potential in the form of a large share of professionals and technician in their workforces ;

3) sectors which have the highest employment potential.

Three skill sectors ranking among the top 5 by all three indicators are: Business and administration; Engineering and engineering trades; Manufacturing and processing. A survey of 100 companies by the Kosovo Chamber of Commerce resulted in a list of 15 most demanded occupations by the private sector : Accountant, Market analyst, Sales agent, Welder, Interior Designer, Food Technologist, and so on. Also, there are number of other reports providing information on skills gaps in specific sectors.

Need for responding to demand for skills is underlined in all Kosovo strategic documents addressing improvement of the situation in the VET Sector with respective measures clearly described. However, VET system fails to provide students with the skills demanded in the labour market. Not only curricula do not match the changing need in the labour market, but profiles offered in vocational schools are not based on the need of the local market.

Proposals for enrolment of students in existing profiles and for opening new profiles come from schools and are supposed to be based on the need of the local labour market which is not always the case. Proposals are endorsed by respective municipalities or AVETA (for 6 schools operating under its authority), and reviewed by MEST VET Division. It is reported that the review if often characterised by formalism resulting in approving new intakes in profiles not demanded by the labour market or offered by schools which do not meet minimum quality standards. Nevertheless, in the last two years MEST did not approve introduction of new profiles if the respective occupational standards were not in place.

Recognition of non-formal and informal learning is at early stage and is expected to see implementation in 2019. The current focus is on accrediting institutions that will have right to carry out the recognition process.

Recognition of qualifications and periods of schooling abroad in the Pre-University level is carried out by MEST . If programme is of the same duration as in Kosovo and curriculum matches the Kosovo curriculum at least 70%, then the qualification or period of schooling is recognized, and the applicant is not required to take any additional exam. Otherwise, the applicant may need to take additional exams as determined by a 3-member committee established by MEST. During 2017, MEST issued 1,400 decisions on recognition of Pre-University qualifications or periods of schooling, and none of them was appealed by applicants

B.1.8 Supporting migrants and refugees through VET

In September 2010, the Government established the Reintegration Fund to support the sustainable reintegration of repatriated citizens of Kosovo by dedicating the budget by years: € 2 mil. were allocated for 2016, for 2017 - € 2,8 mil., whereas for 2018 - € 2.9 mil.

Since 2012, MIA as the funding agency, in cooperation with MLSW and UNDP, as implementing agencies, have implemented activities in support of training and employment of persons repatriated within the Active Youth Labour Market Programme in Kosovo. In February 2016, these activities were extended to include all repatriated persons, by offering them opportunities for training and employment through the Active Programme of the Youth Labour Market in Kosovo. The reintegration programme provides financial support for business plans of repatriated persons who meet the criteria set in the Regulation GRK No. 04/2016 on Reintegration of Repatriated Persons and on Managing the Reintegration Programme, as well as other forms of ALMM including vocational training, internships, wage subsidy and so on.

MEST approved specific bylaws which serves to facilitate integration of repatriated children in the system of schooling in Kosovo . Improving the access for repatriated persons to early and lifelong learning and vocational training is one of the specific objectives of the Strategy for re-integration. Number of readmitted persons during 2017 was 4,509, whereas 2,608 persons benefited from different schemes of the programme for reintegration of repatriated persons.

Unfortunately, data on support to re-integration are not disaggregated by type of support, neither any study on the impact of such support was conducted. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that upskilling is not the primary key to successful re-integration of repatriated persons as long as it does not guarantee access to a job.

B.2: Entrepreneurial learning and entrepreneurship

Identification of issues

B.2.1 Job creation and VET

According the Labour Force Survey for Q2/2018, share of the self-employed among current employees is quite high – 21.3% ; however 63% of the self-employed (13.4% of total number of employees) have no other employees and are considered to have unstable employment. Despite efforts to promote self-employment and entrepreneurship, there is no evidence that VET contributes significantly to job creation in Kosovo. This may be due to the missing system for tracking VET graduates, but our informants agree that VET in Kosovo mainly reacts to the demand from labour market, rather than creating a demand. In the given context, job creation precedes education for specific jobs, whereas VET, to some extent, closes the gap between the need for new skills and current skills.

Description of policies

B.2.2 VET policies to promote entrepreneurship

As traditional job-for-life career paths become scarce, entrepreneurship provides an additional way of integrating people into today’s changing labour markets and improving their economic independence. For some people, self-employment provides income, self-reliance and a dynamic path for growth and the development of human capital. In addition, entrepreneurs may be more responsive to new economic opportunities and trends. However, entrepreneurship is not for everyone, and those who wish to enter self-employment face obstacles to starting and running a successful business. Entrepreneurship is not by itself a solution to the problem of unemployment; it should be seen as an important complement within broader employment and investment climate policies. What makes youth entrepreneurship unique, and different from working with adults, is that young people typically have fewer experiences to draw on, less access to capital for starting up and expanding activities, a reduced number of community contacts and networks, and less knowledge of how businesses operate.

Increase of employment through active labour market measures, with a focus on self-employment and entrepreneurship is one of the objectives of the current Kosovo Government programme , also reflected in other key strategic documents in form of ALMMs, already discussed in section B1.6 of this Report. VTCs offer an entrepreneurship course for unemployed which lasts about 40 class hours and is spread out in two weeks, and is based on ILO’s Start and Improve Your Business (SIYB) Programme .

Self-employment and entrepreneurship development have been widely supported by donor-funded projects as well, resulting in training more than 4,000 beneficiaries with some of them having received financial support for their start-ups.

Youth Employment & Skills (YES), one of the currently running projects, will provide 50 entrepreneurship training grants and 10 grants to support new business start-ups. However, while the system to produce new companies is well functioning, the mechanisms to support the start-ups at later stage, to increase their chances of survival and facilitate their growth, still remain under-developed.

Also, within the scope of ALMMs, EARK operates a self-employment programme which includes training for entrepreneurship, grants for self-employment and mentoring support for beneficiaries. The 2017 budget of € 380,000 was sufficient to support 35 beneficiaries or 0.04% of registered unemployed, lagging considerably behind all other countries in the Region.

On the Education System side, “development of entrepreneurship and use of technological skills” is defined as one of the aims of education in the Kosovo Curriculum Framework (KCF). Consequently, entrepreneurial education is an important part of one of the seven learning areas of the KCF – Life and Work. As stated in the KCF, “in its narrower meaning, Entrepreneurial Education aims at preparing children and young people to undertake an entrepreneurial role in the economy, i.e. to create their businesses. In its broader meaning, it aims to equip children and young people with entrepreneurial skills, such as taking initiative, decision-making, risk-taking, leadership, management and organisational skills”.

Based on the Core Curriculum for Upper Secondary Education and available grade curricula , entrepreneurship is taught in gymnasia within the subject Information and Communication Technology. In vocational schools, it is taught as separate subject in some profiles of the Business and administration area, whereas in some other cases it is integrated in the curriculum.

‘Open floor’

As indicated in section B1.1, youth unemployment rate in Kosovo continues to be very high – 55%, as well as the share of young people not in employment, education or training (NEET) – 30.2%. This is accompanied by low level of registration of unemployed youth with the Kosovo Public Employment Service and limited benefits from active labour market measures.

Only 19.4% of the registered job-seekers in Kosovo are young people aged 15-24 as opposed to 23.5% of registered job-seekers in FYROM, 24.5% in Serbia and 35.7% in Montenegro. On the other hand, only 4.1% of youth registered in employment offices in Kosovo hold tertiary qualifications as opposed to 22.8% in Serbia, 29.6% in FYROM and 40% in Montenegro.137 This may suggest that young people in Kosovo do not have high expectations from the public employment service.

Youth constitute the largest group of beneficiaries from ALMM - 39.6% of participants in vocational training and 33.9% of beneficiaries from other ALMMs are young people aged 15-24. However, ALMM in Kosovo have a very limited scope and the share of youth benefiting from ALMM is very low compared to other West Balkans countries: 5.3% of young job-seekers benefit from ALMM other than training as opposed to 33.9% in Serbia and 36.6% in Montenegro.

At current rates of expansion and forms of ALMMs it is going to take many years for the improvement to be felt. Therefore, the Government must find ways to reach out to inactive and unemployed youth and put them in the active labour market measures in order to improve their chances for employment.

Another complex problem in the Kosovo context is the long-term unemployment. In 2017 the share of unemployed persons since 12 months or more in the total active population reached 71.5% (Table 9), which is still below the level of some countries in the Western Balkans.

Table 9. Long-term unemployment rate in Kosovo

The high and persistent share of long-term unemployment is an indication of the structural nature of unemployment in Kosovo. Those affected run the risk of skill loss, reduced motivation to search for employment, and possibly exiting the official labour market altogether.

Summary and analytical conclusions

1. Policy challenges

High unemployment and weak job creation. – Although the unemployment rate in Kosovo decreased from 30.4% in 2017 to 29.4% in the second quarter of 2018, a deeper analysis shows that this was not due to creation of new jobs, but to increased inactivity rate which rose from 57.2% in 2017 to 59.6% in Q2/2018. In the same period, the employment rate (employment to population ratio) decreased from 29.8% to 28.5%.

Marginalization of the most vulnerable groups in the society. – From the perspective of employment, the gender gap is very high – only 12% of working age women are employed compared to 44.8% of working age men. On the other hand, 82.6% of the working age women are inactive compared to 36.9% of working age men. Youth unemployment rate in Kosovo continues to be very high – 55%, as well as the share of young people not in employment, education or training (NEET) – 30.2%

Shortage and mismatch of skills. – Many companies report problems hiring new employees, largely because of insufficient experience or skills, and consider this kind of constraint as impediment for their growth. Well-established and export oriented companies emphasize the need to make significant investment in providing remedial training to their staff. Kosovo businesses have already expressed their concern for shortage of skills in the sectors of Construction, Health and Hospitality, which is largely attributed to migration. Also, there is a strong perception that this trend will continue due to the needs of developed countries for skilled labour force, with those unskilled risked to be left behind.

2. Factors contributing to policy challenges

Despite the economic growth of 4% in 2018, the capacity of Kosovo Economy to create jobs remains limited due to the current economic structure, largely based on unsophisticated and lower value added products and services, which is unable to create sufficient number of jobs. Also, more than 90% of businesses in the private sector are micro enterprises with less than 10 employees, characterised by slow growth.

The main reasons for high inactivity rates among women are family responsibilities, poor provision of child/elderly care service, and also employers’ biases. Limited absorption capacity of the labour market and inadequate skills of young people are major factors contributing to their exclusion from the labour market.

The links between the Kosovo’s economy and the country’s education system are still weak. The private sector still has difficulties to define its needs, and the schools – both for VET and HE – are not yet in a position to provide the labour market with potential employees who had undergone practice oriented training and whose skills make them immediately attractive for future employers. We have analysed enrolment data by Regions for the three fields which account for almost 80% of students: Business administration and law; Engineering, manufacturing and construction; as well as Health and welfare. In all three fields considerable discrepancies in enrolment among the seven Kosovo regions are observed. Due to the lack of tracer studies it is difficult to conclude how are these differences reflected in employability of graduates, but the differences among regions cannot be explained by trends in local economy.

3. Solutions and progress with implementation

Improving regulatory and business environment is a key to economic growth and job creation, and a durable solution to reducing inactivity and unemployment. Despite recent progress in the Doing Business Ranking, the business environment in Kosovo is weak mainly due to poor governance, an erratic and insufficient supply of electricity, and lack of an adequately trained workforce. The perception of a weak “rule of law” impedes initiatives for foreign investments and supports small scale low value added production, instead of more competitive companies.

Access of young people and women to the labour market can be increased through provision of quality employment services, active labour market measures and support to self-employment. Although improvement of services for vulnerable categories is a strategic priority for the MLSW and EARK, registration of youth with the public employment service in Kosovo is the lowest in the West Balkans Region, indicating that young people do not have high expectations from this kind of support. Youth constitute the largest group of beneficiaries from ALMMs, but the number of beneficiaries from those measures in Kosovo is very low compared to unemployment, so the share of unemployed youth benefiting from ALMMs in Kosovo is the lowest in the Region. The same applies to those opting for self-employment, in which only 35 registered job-seekers received support through a specific self-employment programme operated by EARK within the ALMMs.

Improved education providing skills demanded by employers leads to higher employment. First of all, demand for skills is not identified in a systemic way, but rather through ad-hoc research projects implemented with donor support. On the other hand, need for responding to demand for skills is underlined in all Kosovo strategic documents addressing improvement of the situation in the VET Sector with respective measures clearly described. However, VET system fails to provide students with the skills demanded in the labour market. Not only curricula do not match the changing need in the labour market, but profiles offered in vocational schools are not based on the need of the local market.

4. Recommendations

- Improve the business environment

National Development Strategy 2016-2021 has identified the need to improve the rule of law and infrastructure as pre-requisites for economic development of the country. Kosovo faces considerable challenges in the effectiveness of public services and judiciary which discourages foreign direct investment in the country’s economy. Also, significant improvement is needed in ensuring stable supply with energy and providing a cost-effective transport infrastructure. Other measures include improved access to finances for domestic companies and providing incentives to foreign companies willing to invest in Kosovo. Reducing informality is an important aspect of improving the business environment, since the large scale of informality discourages businesses from investing and hinders economic growth. This can be achieved by improving the labour and tax inspections, and introducing policies encouraging transition to formal market, primarily by pulling off constraints which limit the creation and development of businesses, and removing disincentives to declare work on both the demand and the supply sides.

- Improve the quality of employment services

The MLSW Sectoral Strategy 2018-2022 anticipates a series of measures to improve the quality of services for unemployed: building capacity of the Public Employment Service by means of staff training and improvement of infrastructure; expanding and diversifying the employment services by offering timely information for job-seekers and career counselling for them; making the recently introduced Labour Market Information System (LMIS) fully operational, and so on. Another steps towards improving the quality of employment services are: improving collaboration with the private sector to assess the market needs for specific skills and match those with the profile of job-seekers; introducing an online job platform to attract more young people to register with Employment Offices; setting gender disaggregated targets to increase the employment of women.

- Expand the scope and improve the quality of ALMMs

Active Labour Market Measures should be expanded to reach more job-seekers with particular focus on most vulnerable groups: long-term unemployed, youth and women. Capacities for provision of ALMMs with the highest returns in terms of probability of employment, should be increased and such measures re-designed accordingly. This may require an impact evaluation of ALMMs, but, nevertheless, it is clear that more opportunities for self-employments, internships, on-the-job training and combined training in companies should be provided.

- Align VET programmes to the demands of the labour market

As the first step, more attention should be paid to forecasting of skills demanded by the labour market. This requires more intense communication between institutions responsible for Education& Training on one side and the business sector on the other side. Such communication can be facilitated by strengthening existing consultation mechanisms at policy level (e.g. Council for Vocational Education and Training) as well as at institutional level (e.g. “industrial boards” of education&training institutions). The Government should make use of all research reports identifying demand for skills in various trades, and also commission research when need arises. Review of the VET curricula should be carried out in close cooperation and with active participation of the business community. The Government should carefully review the programmes offered by the public VET providers to ensure that profiles and enrolments match the needs of the labour market.

- Promote entrepreneurship learning in schools

Entrepreneurial education helps young people develop new skills that can be applied to other challenges in life. Non-cognitive skills, such as opportunity recognition, innovation, resilience, teamwork, and leadership will benefit all youth whether or not they intend to become or continue as entrepreneurs. The Education System is responsible for teaching entrepreneurship in the most suitable way, and therefore the inclusion of entrepreneurship-related topics within the ICT course should be re-considered. Entrepreneurship courses should rather have modular structure and can be offered to secondary students within the regular classes or as an extracurricular activity.

Building block C: Social environment and individual demand for VET

Building block C focuses on people – on the young people and adults who could, should or do participate in VET – and the demands and expectations they might have as actual or prospective participants in VET. The questions in this building block discuss problems and solutions in VET from the point of view of individual demand for education and training, structured along the lines of the social rights of individuals to access and participate in education and training, to enjoy equal opportunities to succeed there, and to find fulfilling employment.

C.1: Participation in VET and lifelong learning

Identification of issues

C.1.1 Participation

A major challenge VET is faced with resides in its poor attractiveness: VET is mostly the second best choice, and when someone attends a VET school, he or she usually does so with the prospect to obtain a Matura which provides access to tertiary studies – the actual goal of the vast majority of all Kosovan youth. In the school year 2007/08, 58.4% of secondary students were attending VET schools , whereas one decade later, this share dropped to 52%. Today, IT, Business administration and Health profiles are able to attract more students, whereas a number of other profiles demanded by the labour market struggle for students. Secondary VET schools operate in all 38 municipalities, but with limited number of profiles, so a considerable number of students choose to enrol in schools located in other municipalities.

In last few years there is increased demand for EQF level 5 tertiary programs, since EQF level 4 qualification is not always sufficient for employment. National Qualification Authority accredited 23 such programs, mainly from the field of ICT and finances, offered by nine different providers.

Programs offered by VTCs are open to registered jobseekers only, and for certain profiles the interest is extremely high. According to data provided by EARK, 1,694 jobseekers were on waiting lists in September 2018: 491 in the Hairdressing profile, 406 in Cooking, 206 in Baking & Pastry, 213 in Tailoring, 180 in Construction and so on.

Table 10 shows that participation in lifelong learning is still far below the EU average of 10.9% (2017) , and has been stagnant in the last four years. This requires deeper studies on the causes of such stagnation and measure to address them.

Table 10. . Participation in training/lifelong learning (% aged 25-64)

C.1.2 VET opportunities for vulnerable and marginalised groups

According to the latest Poverty Assessment , about 17.6% of Kosovo citizens live below the absolute poverty line (with less that € 1.82 per day), whereas 5.2% live in extreme poverty (with less than € 1.30 per day). Poverty is particularly high for the following groups: families headed by women (18%), persons with low levels of education (46.1%), people with disabilities (23.5%), pupils/students (26.4%). From the perspective of welfare, they all constitute vulnerable groups. The same applies to Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities who continue to face difficult living conditions . Also, from the perspective of labour market indicators, women and youth aged 15-24 are considered to be vulnerable and marginalised.

With improved access to upper secondary education, the proportion of youth aged 18–24 with at most lower secondary education, who are not in further education or training, has declined (Table 11) with the tendency of closing the gender gap. Current situation is comparable with EU countries like Hungary (12.5%), Portugal (12.6%) and Bulgaria (12.7%) . However, in the Kosovo context, early leavers from education are at a very high risk of being marginalised in the labour market.

Table 11. Early leavers from education (% aged 18-24)