By Shireen AlAzzawi and Vladimir Hlasny

Youths in the Arab region are known to have a hard time transitioning from school to work and attaining ‘good’ formal jobs that have non-wage amenities like stability, social security and paid leave. Youth unemployment in the Arab region is the highest and fastest-rising globally, and work informality is also among the most widespread.

But not all youths face the same predicament. Coming from well-connected, well-positioned and educated families helps a select few graduates, while the vast majority lack the opportunities to get ahead. Children of university graduates almost exclusively work in formal jobs in the public or private sector, while those of less educated fathers are more likely to be informally employed or unemployed.

Important gaps also exist between genders whereby young men are typically channelled to precarious or unsafe jobs, and women are largely excluded from work opportunities. This yields substantial gender gaps in the returns to education and in individuals’ incentives to invest in their human capital.

Youth not in transition

Youths rarely move up the job ladder. Once youths land their first job, another obstacle is to move up the occupation scale. Lack of job mobility is a common theme among youths across the region. Those who start out in vulnerable jobs are unlikely to move to better-quality jobs over time. In fact, some even move “down” to informal jobs, especially those who started as self-employed or employers.

The workers’ subsequent experiences have an avalanche effect on their lifetime outcomes. Gender gaps, wealth effects and parental education effects follow workers dynamically throughout their careers, casting doubt over the equality of opportunities or intergenerational and lifetime mobility.

Family wealth in particular influences workers’ career-long job mobility even after they have accumulated substantial work experience – such as 20 years in the case of Egypt.

COVID-19 provided yet another stumbling block

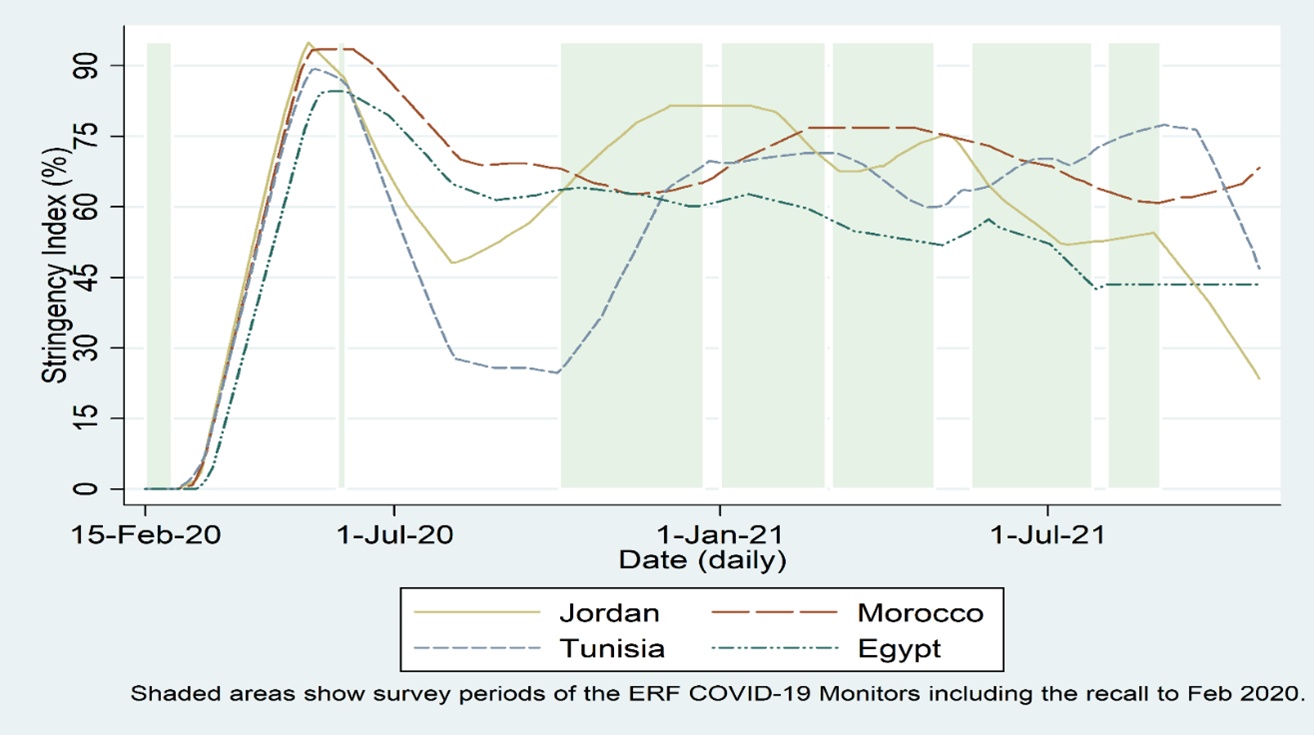

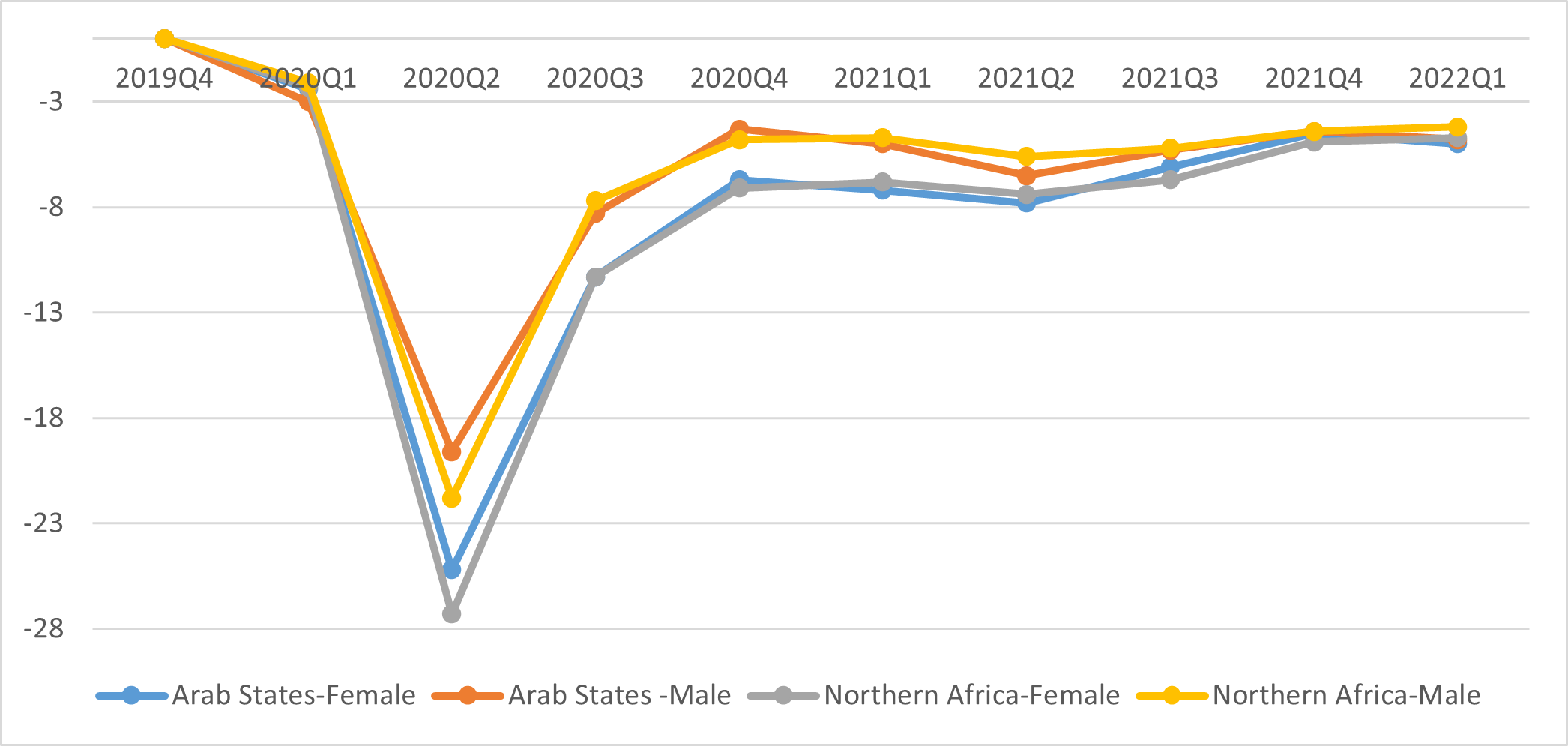

The pandemic perpetuated youths’ vulnerabilities and the inequality of their opportunities. The fall in aggregate demand and strict lockdown measures implemented during the second quarter of the year 2020 through to the first two quarters of 2021 (Figure 1) affected most groups of workers negatively, in Northern Africa more so than in the Middle East (Figure 2).

Figure 1. COVID Stringency index, 30-day moving average, by country and date

Note: Shaded areas show periods with survey information on workers.

Source: Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker.

Figure 2: Percentage of working hours lost due to COVID-19, by sex

Source: ILO modelled estimates.

The Economic Research Forum (ERF) COVID-19 MENA Monitors – rapid assessment surveys conducted in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia – confirm as much. In Egypt and Tunisia, far higher shares of workers faced temporary layoffs over the course of the pandemic compared to the other countries.

Egypt had the highest share of permanent layoffs and also had the highest share of workers who endured a decrease in hours. Morocco had the highest share of those who were no longer wage workers, either exiting the labour market or becoming self-employed.

In Tunisia, notably, a large share of those who had been formal private sector wage workers in February 2020 transitioned to the informal sector, and in the case of women became unemployed or exited the labour force.

Employers’ drive toward cost-cutting, irregularisation, and gig and platform employment have disproportionally affected those whose jobs could not be performed remotely, which cover a large share of youth and female workers, due to the nature of their occupation, or due to lacking access to the necessary technologies.

Youths and women thus trailed non-youths and men throughout the pandemic, perpetuating existing inequalities along the age and sex lines. Jordanian and Egyptian youths faced a similar outlook as older cohorts, while Moroccan and Tunisian youths endured marginally worse prospects. Those with lower education and work experience were also more prone to losing hours, pay or their job, and to remaining jobless.

A bumpy and patchy way out

The second year of the pandemic saw a gradual recovery, but large shares of both men and women who had worked in February 2020 still remained out of their jobs.

Informal wage workers faced a decline and then a recovery in their wages, but no recovery in their hours worked by June 2021. Self-employed workers, informal workers outside establishments, and farmers also continued to experience income losses between February 2020 and June 2021.

By June 2021, men’s employment prospects somewhat recovered, but women remained predominantly out of the labour force. A break from service caused by COVID impaired youths’ and women’s ability to get permanently back on their feet, particularly in terms of job quality.

By the same token, the economic recovery seen in Q3–Q4 of 2021 may not have fully offset the harms inflicted on vulnerable workers during the prior eighteen months, as their skills became rusty, and employers reoriented to prioritising the more experienced formally-employed workers.

Where next from here?

Fixing youth unemployment and informality, and job immobility in general, is vital in a society facing a youth bulge. Part of the solution is in the hands of the workers. Skills, as measured by education, take centre stage in improving workers’ employment prospects, followed by work experience and proximity to market activity hubs (especially clearly in Egypt and Morocco).

Regional governments, and their international benefactors, could support workers by designing upskilling and reskilling programmes matching private-sector demand, and providing stronger incentives for decent job creation.

Indeed, much lies outside of workers’ control. Authorities should tackle the proliferation and social acceptance of job precariousness. More effort should go into enforcing occupational safety, non-discrimination, health and job security, and strengthening social protection.

A broader and more generous system of social assistance should sustain and lift those stuck behind. Building comprehensive social protection floors should be explored as a tool for mitigating vulnerability. Piloting targeted basic income programmes and employment guarantee schemes would be a good start.

These measures could all speed up the job recovery from the pandemic and other shocks, and lay the foundation for more inclusive, dynamic and fulfilling conditions in labour markets.

Please log in or sign up to comment.